Hi! I’m Lachlan Sims, a professional tutor.

On this page, you can read a little bit about my experience with some of my favourite topics in this area, as well as some common areas that my students typically need improvement!

Hopefully you find it very informative.

Quantum Mechanics | Astrophysics | Circuits | Special Relativity

Quantum Mechanics

This topic is really fun because you can learn it from so many different perspectives. Unfortunately, most physics students never get to learn any Linear Algebra before having a crack at QM - which I personally think should be a crime… I promise you would be amazed how much it immediately clarifies so many subtopics! I like to think that QM is basically just statistics with a Linear Algebra wrapping, at least from a typical undergraduate level perspective.

I have had the pleasure of learning QM from the ground up no less than three times. I have covered units on QM at both UWA and at Cardiff University in Wales, as well as going over Leonard Susskind and Art Friedman’s fantastic book “Quantum Mechanics: The Theoretical Minimum” with a mathematics PhD student, who had no previous experience with physics really at all. The last of those was one of the best ways of learning I have personally ever experienced - the pure mathematician was so much more rigorous than any of my lecturers had ever been, and made me question everything. It was so much fun to cover everything from a totally different perspective. I found myself using very ‘cheap’ explanations and was forced to reconcile this.

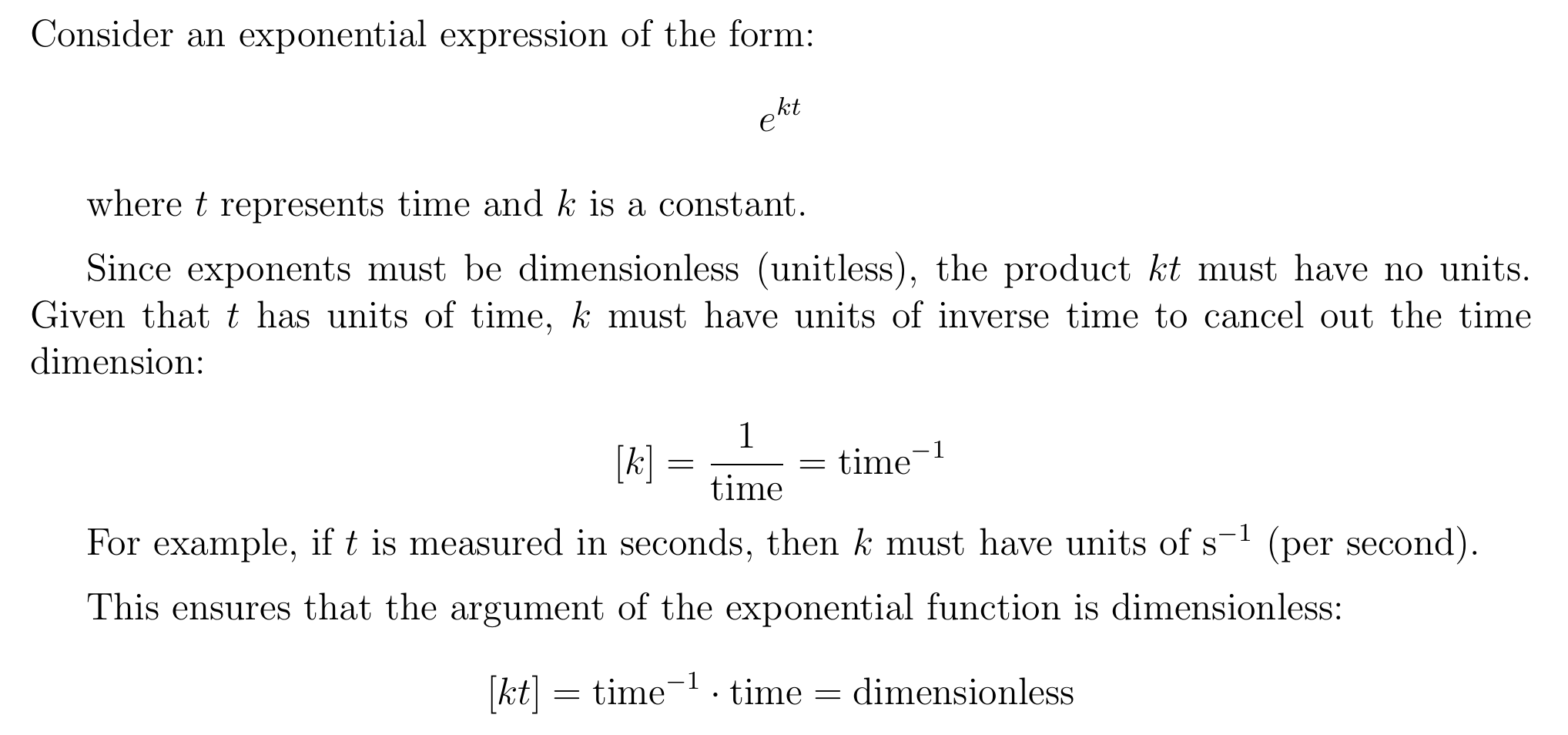

One such ‘cheap’ explanation was telling the mathematician that “the exponent must be unitless, therefore the coefficient here must have units of blah”. I.e.:

He found this hilarious, and although I was right about the units and that the power indeed must be unitless to make any sense of the expression at all, I was forced to concede that it really was quite an absurd way of deriving it. I love a bit of dimensional analysis as much as the next guy, but there’s usually something about it that feels a little too ‘intuitive’ to be genuinely rigorous. Though my students usually love tricks like these, I would caution you to think very carefully about how you knew each little variable’s units - was it an educated guess? If so, maybe consider an alternative method, just as an exercise for your brain!

Everybody’s wrong about ‘Schrödinger's cat in a box’!

This was meant to HIGHLIGHT THE ABSURDITY OF SUCH AN INTERPRETATION - but most media ended up completely misrepresenting it as to what QM means about our reality. It is of course utterly ridiculous to think that a cat could be both alive and dead at the same time. Or… is it? (hence the opinionated and extremely controversial ‘interpretation’ part of the astonishing mathematical results derived in QM). Anyway, if this ‘philosophy of science’ interests you as much as it does me, you should really read Thomas Kuhn's “Structure of Scientific Revolutions”. Effectively we can sometimes end up accepting totally absurd things just because they become the status quo. I think this is a shame... and a little scary!

Is light a particle or a wave?

The answer is not “both”, but rather something like:

Light has a dual nature; it behaves as both a wave and a particle - hence it is neither, but rather something else entirely that has the behaviours which we observe, and for which we have no name

Easy, right? (ha!). I am sure some exceedingly lazy teachers have just succumbed to the difficulty (which I understand at a certain level, but I of course still despise) and simply taught you that light is ‘both a particle and a wave’. Please do your best to rid yourself of this notion. Interpreting results, both theoretical/mathematical and experimental, is really, really, really hard. It should not be taken lightly. This revelation that light, something we feel as though we understand very well, is in fact so complex that we literally cannot define it as a particle or a wave, should hopefully be quite a striking one to the uninitiated. That’s not even to mention the fact that it turns out all matter behaves this way, but we just happen to notice it more easily for less massive, subatomic particles! At the end of the day, this ‘duality’ is just a name attributed to the issue that classical mechanics is incompatible with observations, and one is forced to use quantum mechanics!

Astrophysics

Any of my previous students reading this know that I am not overly fond of the number of assumptions that are (necessarily) made whilst studying such complex macroscopic systems. However I acknowledge that these assumptions generally do need to be made, and if you do a deep dive into their justification, you will actually almost always find that they are indeed reasonable assumptions. Reasonable meaning that they do not lead to huge errors (sometimes due to some unanticipated, strange cancelling out of effects). So, I suppose that my real issue is just that it’s a complicated topic which is very difficult to thoroughly and neatly (so satisfyingly) explain from the beginning. How do you get through explaining the Virial Theorem without getting lost on seventeen different tangent explanations along the way? Make assumptions that may even seem quite tenuous at first glance - I, along with apparently every lecturer I’ve been taught this topic by, agree that this is pretty much the ideal way to make it through in a timely and natural manner. There’ll be time to clarify things later, after all! But it can still be frustrating for students to accept these simplifications, of course. And it can be even harder to understand when to make those assumptions, since that’s not really ever taught!

Astrophysics is really unique because it forces you to dabble in different fields from time to time, just to dip your toes in. You have to grapple with topics ranging from quantum tunnelling & energy eigenstates (to understand why stars which run out of fuel do not immediately collapse, we must understand so called ‘degeneracy pressure’, which is a fascinating concept) to black holes and gravity at extreme scale. It’s also a very exciting field with a potential fair amount of engagement with real world data even at the undergraduate level, which is relatively rare in undergrad physics! Not to mention it is surprisingly easy to ask questions that we don’t yet have a proper answer to - which is always a thrill!

Explain quantum tunnelling without QM

This one’s easy. Here’s how it goes:

There’s uncertainty in a particle’s position that exceeds the classically allowed region - therefore, it must be possible for the particle to appear where it is classically forbidden

I hate this explanation, personally - and not just because it’s cheating the student out of some beautiful linear algebra. But I’ve seen it from multiple different professors at different universities - it’s a very common way in astrophysics to avoid getting into the nitty gritty whilst still ‘explaining’ why that particle can be in one spot when it seems impossible. I struggle to narrow down exactly why I dislike this so much, except that something about it just seems cheap. I can’t help but imagine this similar argument:

Take a really imprecise ruler - one where each marking is every 10 cm. Hence, whenever you measure the length of something using that ruler, you have an absolute uncertainty of 10cm (twice the usual half of smallest differentiator, since you are technically making two readings - one at each end of the object). Now, you use your awful ruler to measure the length of an object that is quite small, appearing about halfway between the end of the ruler and its first marking.

Well, its length is (estimated to be) 5cm +/- 10cm.

Huh? Wait, so do you mean to say this object could be anywhere from -5cm to 15cm long? Of course not! Ridiculous. You can’t have negative length, that doesn’t make any sense. Er… but hold on, what if I say “but quantum mechanics says weird things can happen”. Is it now suddenly okay to suggest that this is a reasonable conclusion to reach? Now you understand how I feel about the earlier explanation.

I don’t wholeheartedly believe that my example is an appropriate/fair analogy - but this still irks me somehow, that’s for sure! I still believe it is educational to consider it, though - I think the issue lies in understanding that uncertainty can effectively be though of as standard deviation in one’s measurements of the observable. Thinking of in this statistically-minded manner, I think the explanation does become a little more satisfying. After all, the standard deviation could not be so large unless there was a chance of the particle being in the classically forbidden region. (Its probability density function must be nonzero in those regions.) Then there are times when that is clearly not the case - in my extreme example, the PDF must be zero for lengths below zero. So it isn’t reasonable to interpret the 10cm as the standard deviation in that case. Interesting at the very least! (When is it correct to interpret the uncertainty as standard deviation, and when is it not? In this case I made the decision because it led to a ridiculous outcome, yet quantum tunnelling is a ridiculous outcome. Yeesh, my head is spinning. I’ll leave this one as an exercise to the student. Haha, I always wanted to say that.)

Energy Eigenstates and Degeneracy Pressure

Okay, so the Pauli Exclusions Principle basically just says:

Two identical fermions in the same place at the same time cannot be in the same quantum state (they can’t have all the exact same ‘qualities’ as one another).

This means that when you have a star that has no fuel left and is just slowly cooling down (hence its outward thermal pressure caused by the momentum of photons escaping outward - just remaining ‘residual’ heat, no longer from newly generated heat from fusion in the core - is decreasing, and so the gravitational force will surely overcome it sooner or later), we find that it just.. stops collapsing at a certain point. We checked the two battling forces though, and clearly the gravitational force is stronger than the outward thermal pressure at its current temperature. So, what’s the culprit? Degeneracy pressure. It turns out, because of this exclusion principle, electrons (and neutrons, protons and quarks) really don’t want to coexist in the same state - i.e. the same energy eigenstate. So, they stay in a more excited state more often than anticipated. Hence they are more excited than they would have otherwise been, and have enough kinetic energy to keep the star from collapsing. Read the below for more details, if you’re interested:

For white dwarfs (supported by electron degeneracy pressure), the limit is the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 solar masses. Beyond this, the electrons are forced so close together that something dramatic happens: electron capture. The electrons get pushed into protons, creating neutrons and neutrinos:

e⁻ + p⁺ → n + νₑ

This removes the electrons that were providing the pressure, causing catastrophic collapse.

For neutron stars (supported by neutron degeneracy pressure), the limit is around 2-3 solar masses (currently unknown afaik). Above this Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff (TOV) limit, even neutron degeneracy pressure can't resist gravity. At these extreme densities:

General relativistic effects become dominant - gravity gets stronger as density increases

The pressure itself contributes to gravity (via Einstein's equations), creating a runaway effect

Neutrons may break down into quarks, but even quark degeneracy pressure has limits

Once the mass exceeds these thresholds, no known force in physics can halt the collapse. The matter collapses past its Schwarzschild radius, forming an event horizon - a black hole is born.

Circuits

Note: If you are an electrical engineer and/or write functions for the complex Voltage/Current in time, you may not find this useful… If you’re having trouble, book a free consult! I can help.

WOW this topic is taught so universally poorly. Wow. This is just my personal experience, yes, but I don’t think it’s fair to dismiss it completely out of hand - I have seen hundreds of students from Highschool to University from so many different institutions and they all generally suffer from the same problems. (Yes, I only see the students that seek out a tutor, so this is a very biased sample!)

There are so many different shortcuts and “Golden Rules” (yuck) that some professors just straight up, unabashedly ignore students’ protests when they ask if everyone understands what a given circuit does and how it works (this video is hilarious by the way). Anyway, I’m going to stick to straightforward basics, because that is so so commonly where students need work the most!

First of all:

Ohm’s Law: V= IR

In this (and any other) equation, treat V instead as delta V (aka ‘change in voltage’ or ‘potential difference’). Instead of thinking ‘the voltage is X’, try thinking ‘the voltage across this element is X’. Seriously, you wouldn’t believe how important this is! If you really, really embrace this, you should understand why so many people incorrectly insist that power loss should be found exclusively via use of the formula current squared times resistance. When, in reality, you can use any form of the simple Power formula you’d like, just so long as you use the correct Voltage (being the actual voltage used across an element).

This, of course, is all predicated by poor teaching at the high school level.

Another possibly useful way of thinking in this field which I believe to be fairly rare (I was never taught this myself) is to think of voltage as the amount of energy each electron has (in eV) at each point in the circuit. An electron that passed through a 10 Ohm resistor may have used 5 eV to get through, so now it has 5 V less afterwards.

Then once you begin thinking about individual charge carriers being responsible for current flow, you will easily understand the sometimes daunting “Kirchhoff's Laws” - I promise!

The sum of ingoing current must equal the sum of outgoing currents from a given junction? Oh, yeah! We can’t just lose electrons! (conservation of charge)

The sum of voltages in any loop is zero? Well, yeah - the potential difference between a point and ITSELF is of course zero! And another way of finding that potential difference is by following the path an electron could take to arrive back at that point and add up all the changes in energy that electron experiences - including gaining energy! (conservation of energy)

Special Relativity

Please, please watch this video. It is SO good!!

You’d have to be crazy to not enjoy this topic at least a little (or, just be taught by someone completely lacking even a modicum of enthusiasm). Of course this is just so much fun to see people experience for the first time - and then when the relativity of simultaneity is properly investigated (typically in first year) - just, wow! So cool! So crazy weird.

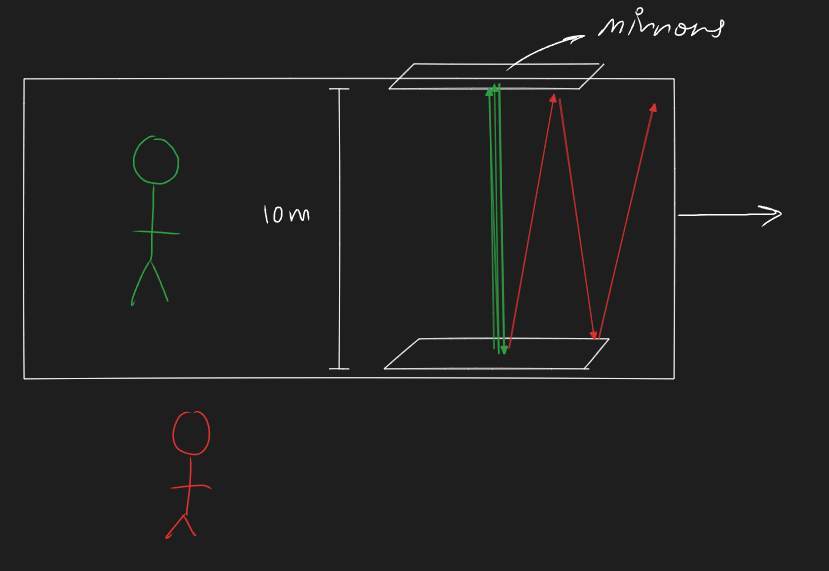

So you’ve probably heard about it, but I can’t exactly go through this without at least covering it a little! So, please feel free to skip to the next paragraph if you’ve already been introduced to the concepts of length contraction and time dilation. The common introduction is remarkably straightforward:

Imagine a spaceship travelling at some constant velocity. Picture two mirrors placed opposite one another within the ship, facing each other. They are arranged so their reflective surface is parallel to the velocity of the ship. Now picture a photon bouncing between these mirrors. From the perspective of someone within the spaceship, it may take, say, 5 nanoseconds for the photon to travel from one mirror to the other. From the perspective of someone outside the ship, looking in, it takes a bit longer - because the light is actually travelling further in their inertial reference frame (diagonally up and to the right, for instance). See image below for reference. Therefore, since they both must agree that the photon is travelling at the same speed, the outside observer must record that it takes longer - say, 6 nanoseconds - for the photon to bounce between the mirrors. Hence, the outside observer’s time is dilated with respect to the observer in the ship’s time. Voila!

Now here is something that not a lot of people are ever explicitly taught: time dilation and length contraction are both just sides of the same coin - you can’t have one without the other! Once I have convinced you of time dilation, you technically should require very little encouragement to appreciate length contraction also! I.e. if an observer (Alice) on earth witnesses a ship (with Bob on board) zoom by at 0.9c (γ ~ 2.3) towards Mars, Alice will see Bob reach Mars after about 30 seconds. For Bob, it will take just 13 seconds. This is simply because, from Bob’s perspective, the distance to Mars is less than half of what Alice measures! These must both be true at the same time - after all, Bob sees Mars zooming towards him at 0.9c. With no other factors to consider, it would take him exactly the same amount of time as measured by Alice. The only way to reconcile the time dilation is by necessarily realising that the distance to Mars is contracted by exactly the same factor, gamma, as the time was dilated for Alice!

Have trouble with Special Relativity Questions?

I have some clear advice that I’d like to offer to you:

Use coordinates in your diagrams! Stop talking about just delta t and delta x - use x1 and x2 for the locations of interest in one person’s IRF and then add a ‘prime’ (aka ‘tick’ - one of these: `) for the other IRF. Do the same for time as well - stop treating time as just a ‘duration’ - it is one of the coordinates of spacetime! You may be surprised how often this helps.

Never simply say something is “at rest”. Instead: “at rest with respect to X”

Don’t bother manually remembering which way around the proper time (duration) and proper length each go in their respective equations - just remember the definitions below, and after finding gamma, the rest will flow easily.

Draw big diagrams, and when finding a distance, draw an imaginary rope connecting the two points - whoever is stationary with respect to the rope for the whole time is the one that can measure the proper length / distance!

For harder questions where you need to understand the relativity of simultaneity - see step 1!! Now read it again! Now go back to easier questions and actually do it this way for practice!! Well done!

What is Proper length?

The longer length (this is an oversimplification but useful in simple questions):

The length of the thing measured by someone who is at rest with respect to the thing.

What is Proper Time?

The shorter time (this is an oversimplification but useful in simple questions):

The time measured by an observer such that the 'events occur' at the same point in space (from their perspective/IRF). I.e. they measure the events to have the same spatial coordinates.